The Case:

A teacher of the Law came up and tried to trap Jesus. “Teacher,” he asked, “what must I do to receive eternal life?”

Jesus answered him, “What do the Scriptures say? How do you interpret them?”

The man answered, “ ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength, and with all your mind’; and ‘Love your neighbour as you love yourself.’ ”

“You are right,” Jesus replied; “do this and you will live.”

But the teacher of the Law wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, “Who is my neighbour?”

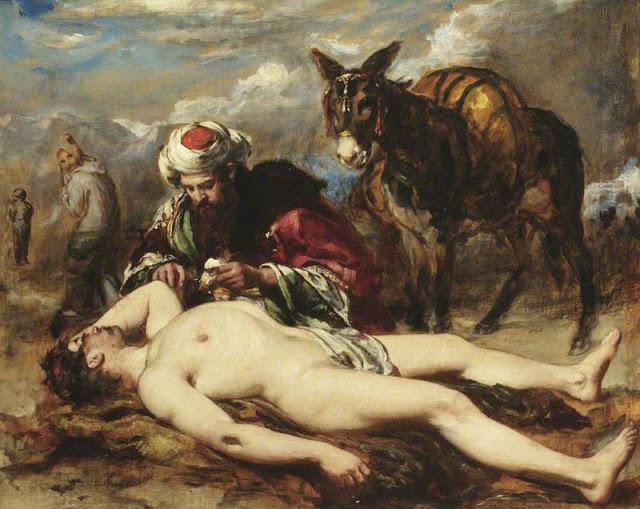

Jesus answered, “There was once a man who was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho when robbers attacked him, stripped him, and beat him up, leaving him half dead. It so happened that a priest was going down that road; but when he saw the man, he walked on by, on the other side. In the same way a Levite also came along, went over and looked at the man, and then walked on by, on the other side. But a Samaritan who was travelling that way came upon the man, and when he saw him, his heart was filled with pity. He went over to him, poured oil and wine on his wounds and bandaged them; then he put the man on his own animal and took him to an inn, where he took care of him. The next day he took out two silver coins and gave them to the innkeeper. ‘Take care of him,’ he told the innkeeper, ‘and when I come back this way, I will pay you whatever else you spend on him.’ ”

And Jesus concluded, “In your opinion, which one of these three acted like a neighbour towards the man attacked by the robbers?”

The teacher of the Law answered, “The one who was kind to him.”

Jesus replied, “You go, then, and do the same.”

My friend, Joe Devlin, a Jesuit priest, said Mass in the zendo at Hartford Street early in 1990. Joe was visiting friends in San Francisco, and I asked him to come by to say Mass for the Catholic men in Maitri Hospice. I told Issan about my plan, and he said he was happy to have Mass and very excited to meet Joe.

It was a Saturday evening. Joe was due to arrive at 5. I was scrambling, assembling a few basics, actually just the essentials, bread, wine and a clean tablecloth for the dining room table. Issan, who was at the time in the final stages of HIV disease came downstairs in his bathrobe, to ask when “Father Joe” was due to arrive, and see what I was doing. After I explained, he said with a big smile, but firmly, “Mass will be in the zendo, not the dining room.” Then he took over and directed all the preparations with the same care that he would have given to a full-blown Zen ritual, the table he wanted for the service, the table cloth, the candles, the cup. He went back upstairs, and when he came down again, he was dressed in his robes. He greeted Joe at the door with a hug and kiss, thanking him for coming, and telling him that Mass would be in our chapel, the zendo.

Issan and five or six of us sat in meditation posture on cushions while Joe improvised the ancient Catholic liturgy, beginning with a simple rite of confession and forgiveness. I noticed that Issan brought the same attention to the Catholic ritual as he did zazen and Zen services. When it came time to read from the Testament of Jesus, Joe took a small white, well-worn book out of a pocket in his jacket, and said that his mother had told him that the story he was about to read contains all the essentials for a true Christian life. Sometimes even Jesuits get their best theological training from their mothers.

Then he read from the gospel of Luke, chapter 10, the parable of the Good Samaritan. For any of you who need a refresher course in New Testament studies, this is a story about a man who is robbed, taken for everything he has, savagely beaten and left by the side of the road to die. All the people who might have helped, even those who should have helped, chose to walk on the other side of the street when they saw him—except for the Samaritan. Now the Samaritan in Jesus’ day was the guy whom good upstanding members of the community might have called the equivalent of “faggot” or “queer.” He was an outcast, but he was the only person who actually stopped and took some real action to help the poor fellow out. Jesus teaches us that real love is shown through actions, not words.

The next morning—Sunday mornings were the usual gathering of the Hartford Street community—Issan began to talk about Fr. Joe and the liturgy. Catholic Mass in the zendo was not universally welcomed. Actually so many members at Hartford Street carried the wounds of discrimination in the religion of their parents that Christianity was rarely spoken about. And the kind Irish priest from Most Holy Redeemer who came to administer the Last Rites to hospice residents who requested it was friendly, but, how can I describe it? sacramentally efficient. However Issan was exuberant. He’d fallen in love with Joe. He said that during the Mass he had the experience of really being forgiven and that had allowed him to feel peace, even appreciation for his early religious training.

Issan had also fallen in love with Luke's parable. He turned to me and asked, “What was the little white book that Fr. Joe read from?” Startled, I said that was the New Testament. “Oh,” Issan said lightly, “it must have been in Latin when I heard it as an altar boy, but it was exactly how we should lead our lives as Buddhists.”

Issan saw Maitri as much more than just a Buddhist hospice, though it was deeply Buddhist to its very roots. He shaved his head and wore a Soto priest’s patch-work robe, he bowed and chanted in Sino-Japanese, but he understood very clearly that real wisdom, what Buddhists call prajna, is not the sole property of any religion. I actually think he took the Teaching of Jesus to a new, heroic level: the definition of friend included building an inn for the injured traveler when he couldn't find one in town.

When Joe and I had dinner together the night before he flew back to Boston, I told him what Issan had said. A few days later, the small New Testament that had been in his jacket for years arrived in an envelope addressed to Issan. Before Issan died 6 months later, during one of our last meetings, he asked me to thank Joe again for the zendo mass after he was gone. I did. And that New Testament which passed from the pocket of Joe’s jacket to Issan’s bookshelf at Hartford Street to my altar, I have since passed on to a person who asked a dharma question about one of the stories in the Gospel of Jesus.